A personal journey to the City of Literature

On October 31, at the tail end of World Cities Day, UNESCO dropped the news: Dumaguete City was now UNESCO Creative City of Literature, alongside Quezon City, which was designated as UNESCO Creative City of Film. I was in the middle of a Halloween party in a Dumaguete hotel when I received the news from my fellow coordinators of this campaign. Forgive me, but I cried. Because this was always a pipe dream that felt possible, and now it was real.

But a pipe dream is comfortable. Indulging in pipe dreams is safe, because there are really no risks involved, only pronouncements. You can just say, “I’ve always wanted to have Dumaguete become a UNESCO creative city” — and some sort of satisfaction gets sated in the recesses of your ambitions. The pronouncement is there, hanging in the air — and somehow that is enough. But it really isn’t.

The best fulfilment of dreams is in the tangible. And there lies the rub: because most of the pursuit of our dreams actually involve risking it all — carving time out of our busy lives to fill out a fragile schedule of creation, despite the demands on our lives from other things we have also made commitments to — like work, like family, like friends; committing to accomplish the dirty work of untangling seemingly insurmountable paper work or bureaucracy, generally sweating out the small stuff; and developing fortitude of spirit, because you will meet constant disappointments, as well as the firewall of unhelpful individuals who do not understand what you want to accomplish.

The road to dreams fulfilled is never smooth, never easy. Pipe dreams, on the other hand, are easy.

One pipe dream I had indulged in for so long was Dumaguete City becoming UNESCO Creative City of Literature. As a writer born and raised in Dumaguete, I know — perhaps in the most personal sense how this city has carved a place for itself as an unlikely capital of the literary arts in the Philippines, helped for the most part by writers from Silliman University, like the Tiempos, who chose to stay in Dumaguete (despite the tangible promises of more fulfilled careers outside of it) and have made it the home for which they could steward, not just their own literary creations, but also foundational institutions that would turn out to be great contributions to the national literature.

But much was at stake. To quote National Artist for Literature Resil Mojares: “In promoting Dumaguete as a UNESCO City of Literature, two things are important. One must see not only the city’s tradition and current status but the award’s potential and prospective value in raising the city’s visibility and promoting further development that will go beyond the literary field to sectors like tourism, education, and the local economy, as well as diffuse outwards to other places in the country. The stakes are high since Dumaguete is the country’s best bet for being a city of literature and I really think that if Dumaguete does not get this honor, it is unlikely that another Philippine city will.”

Iowa beginnings

In 2010, I was one of two Philippine delegates chosen as honorary fellows of the International Writing Program (IWP) in Iowa City, which just became a UNESCO City of Literature in 2008. When I was in Iowa for this very prestigious fellowship, it dawned on me that this distinction was also fitting for Dumaguete. Iowa City is small, like Dumaguete. It only has one major bookstore; same as Dumaguete. It regularly hosts international writers and literary conferences; same as Dumaguete. And it has the same vibe as Dumaguete — replace Iowa’s corn fields with the sea, and you will get Dumaguete, only with blonde people. In fact, Dumaguete writer Rowena Tiempo Torrevillas, who is a resident of Iowa City, calls that Midwestern city as her “blonde Dumaguete.”

Iowa City is also a place whose writing culture is driven by the University of Iowa, the biggest university in town — essentially its own Silliman University. (The writer Robin Hemley, who ran the creative nonfiction program at the University of Iowa for many years, is actually married to a Filipina — from Siquijor.) The famous Iowa Writers Workshop — the grandfather of all writing workshops in America — was the model for the Silliman University National Writers Workshop, the oldest creative writing workshop in Southeast Asia, founded in 1962. In fact, both Edilberto Tiempo and Edith Tiempo, co-founders of the SUNWW, were products of the Iowa Writers Workshop, graduating in the 1950s: Edilberto for fiction and Edith for poetry.

And when Paul Engle, the longtime director of the Iowa Writers Workshop, visited Dumaguete in the 1960s to be part of the SUNWW, the idea of establishing the International Writing Program came to him. He, in fact, invited some of the early alumni of SUNWW to be part of the early batches of the IWP’s famous fall residency. All these literary crosscurrents were already in place when I went to Iowa in 2010 to be part of that fall residency — which is probably why I felt so much at home there.

Small steps

Since I came back from the US, I’d been advocating for the idea of Dumaguete as UNESCO Creative City of Literature every chance I got, including at several editions of the 6200 PopUp, sponsored by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) Negros Oriental, as well as in all my lectures about Dumaguete literature in various seminars and fora, including one on the creative economy at Silliman University, sponsored by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

In 2014, in my capacity as the founding coordinator of the Edilberto and Edith Tiempo Creative Writing Center, I even curated an exhibit at the Silliman Library titled Cities of Literature, which traced the link between Dumaguete and Iowa, with the blessings of the IWP’s Christopher Merrill.

In 2018, prodded by former Dumaguete City tourism officer Jacqueline Veloso-Antonio, I prepared a white paper for Mayor Ipe Remollo to determine whether we should apply to UNESCO for City of Music or City of Literature. (You see, only the LGU can apply for the designation of UNESCO Creative City.) Naturally, as a writer, my bias was clear. But the pandemic put these plans on hold.

When I gave a talk about this very same thing at the first edition of Dumaguete Literary Festival in April 2024, however, this propelled then-DTI Negros Oriental director Nimfa Virtucio to take the first steps and got me involved in the official application to UNESCO, with the blessings of Mayor Remollo. That’s the story. We submitted our application on the deadline: March 3, 2025.

An arduous process

Truth to tell, the UNESCO application, which lasted from December 2024 to February 2025, took such a toll on my mental and physical health, and, by the end, I actually found myself getting sick a lot. The application — in its blank state, composed of eight pages with seven chapters of questions, with each question having their own sub-questions, and each one with a specific character count — looked simple, but soon proved intimidating. The final bid ultimately amounted to about 40 pages of well-considered responses, tackling not just the heritage of Dumaguete specific to literature, but also the plans the LGU has in place to make sure the sector prospers in the coming years. We persevered.

Was it the sheer ambition, the “internationality” of it all, that was intimidating? I guess so. I was so exhausted and anxious I couldn’t even entertain some of the minor blowbacks to the effort from people you would think would be the most supportive of the campaign. (Some people actually thought we were applying for grant money. Where will the money go? they asked. But that’s not what the UNESCO designation is all about. We tried to reach out to many stakeholders in Dumaguete — representing the creatives, the schools, the publishers, the book sellers, the cultural workers — and form them into a technical working group to help us thresh out what the community wants in a creative city of literature. In the end, while we could not control some of the divisiveness, or miscommunication, or benign disinterest, most people in Dumaguete were very kind and supportive, even with last-minute asks.)

In my darkest moments during those months, I actually felt I was so alone. That’s not true, of course. In the end, it was a coterie of friends and associates from Buglas Writers Guild and the Dumaguete Literary Festival who pulled me out of the darkness, and together we made it to the deadline. If there is one person to thank, it would be DTI’s Anton Gabila, who was the steadfast keeper of our light, the rock to all our efforts, never mind the mixed metaphors. There’s also the indefatigable efforts of former city tourism officer Katherine Aguilar, who provided the grease to get the LGU involved in the entire process.

In the end, we did become UNESCO Creative City of Literature. I will take the road of gratefulness. I have always believed in the magic of trying instead of wishful thinking and pipe dreams; this was our attempt to make things tangible. And we were justly awarded for the effort. – Rappler.com

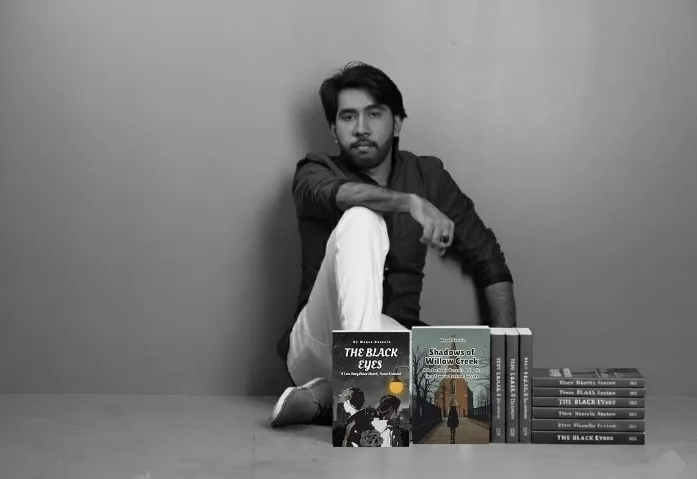

Ian Rosales Casocot is the author of Don’t Tell Anyone, Bamboo Girls, Heartbreak & Magic, and Beautiful Accidents. He has won the Palanca nine times for his fiction, plays, and children’s poetry. In 2008, his novel Sugar Land was longlisted in the Man Asian Literary Prize. He was writer-in-residence for the International Writers Program of the University of Iowa in 2010. As president of Buglas Writers Guild, he was the lead coordinator in the campaign for Dumaguete to become UNESCO Creative City of Literature. He is based in Dumaguete City.

link